About

Young people rarely get the chance to think critically about futures in school and when they do, the dominant narratives they encounter come from governments and popular media, not from their own communities or experiences. Meanwhile, history education routinely treats the past as a chain of events to memorize, with an untested assumption that understanding history will naturally produce skills to act in the present and future.

This thesis challenged that assumption. Working within a 9th-grade U.S. history curriculum, I designed and piloted a futures-thinking curricular module that helped high school students connect historical inquiry to the futures they want to build. The goal was not to teach students to predict, it was to help them recognize that their values, choices, and actions shape what comes next, and to give them structured methods for doing that thinking.

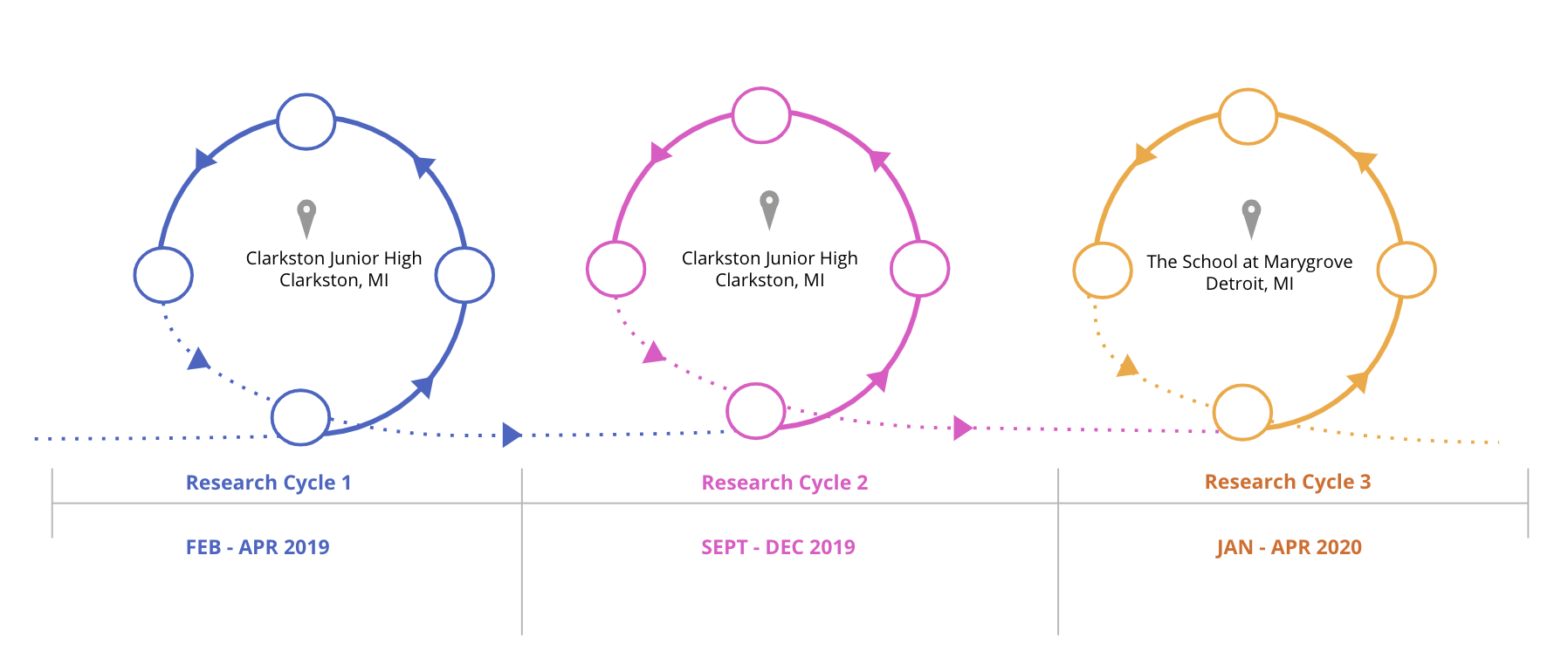

The module was piloted across three iterative research cycles in two classrooms in southeastern Michigan, engaging over 130 students.

Process

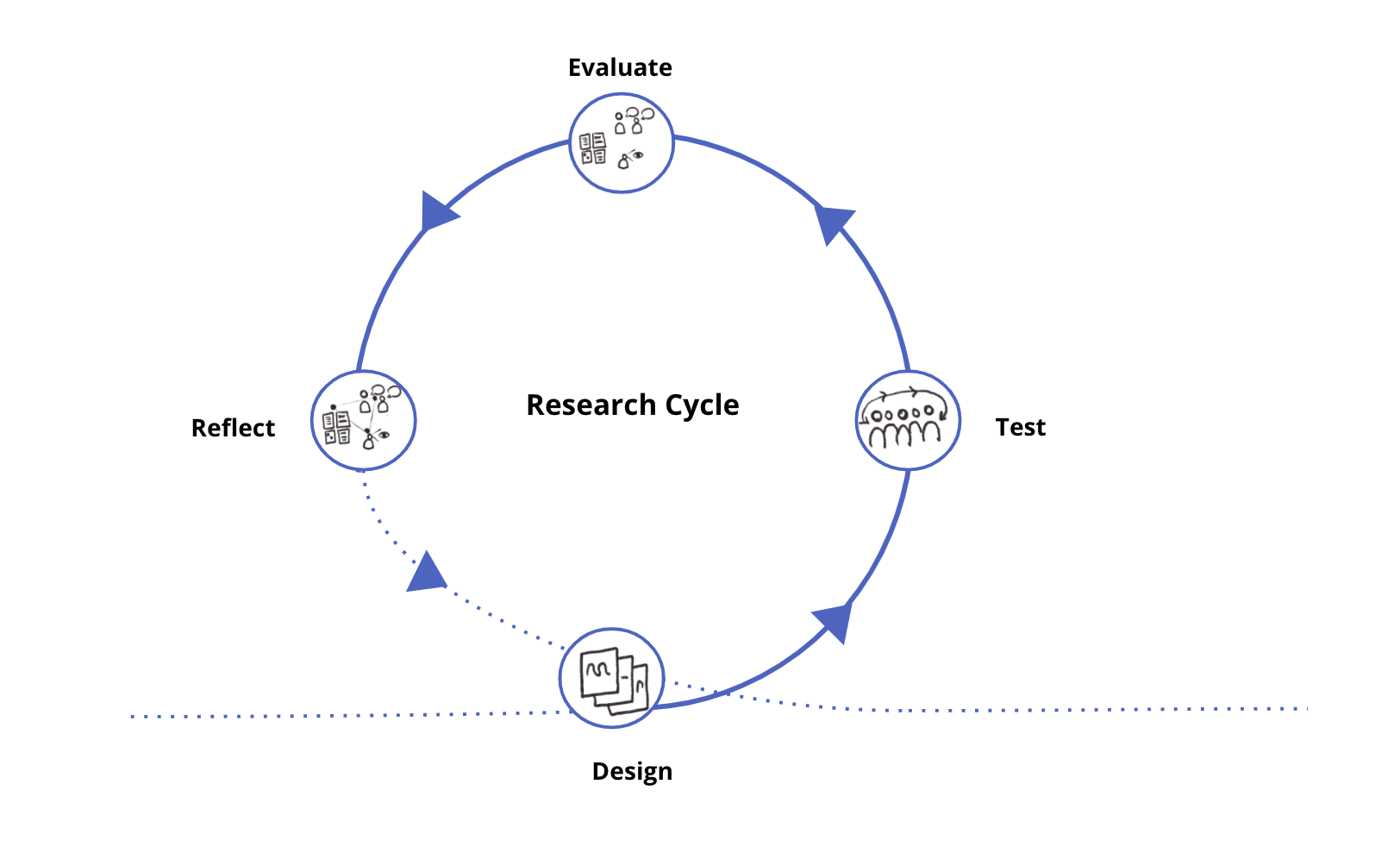

The project used a hybrid methodology combining Design-Based Research, Participatory Design, and Design Justice; an integrative approach where design methods served as cognitive tools for students, not aesthetic outputs.

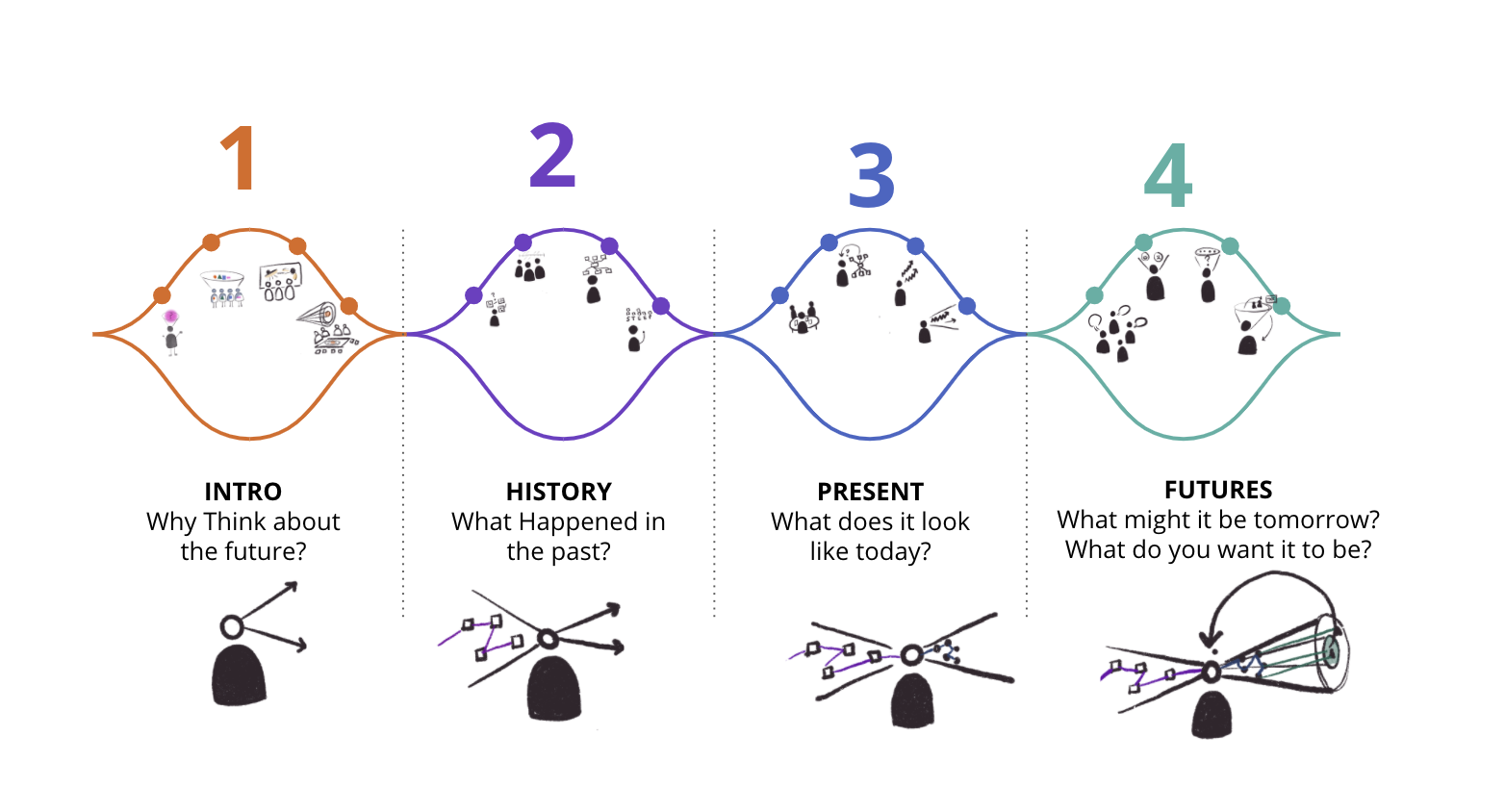

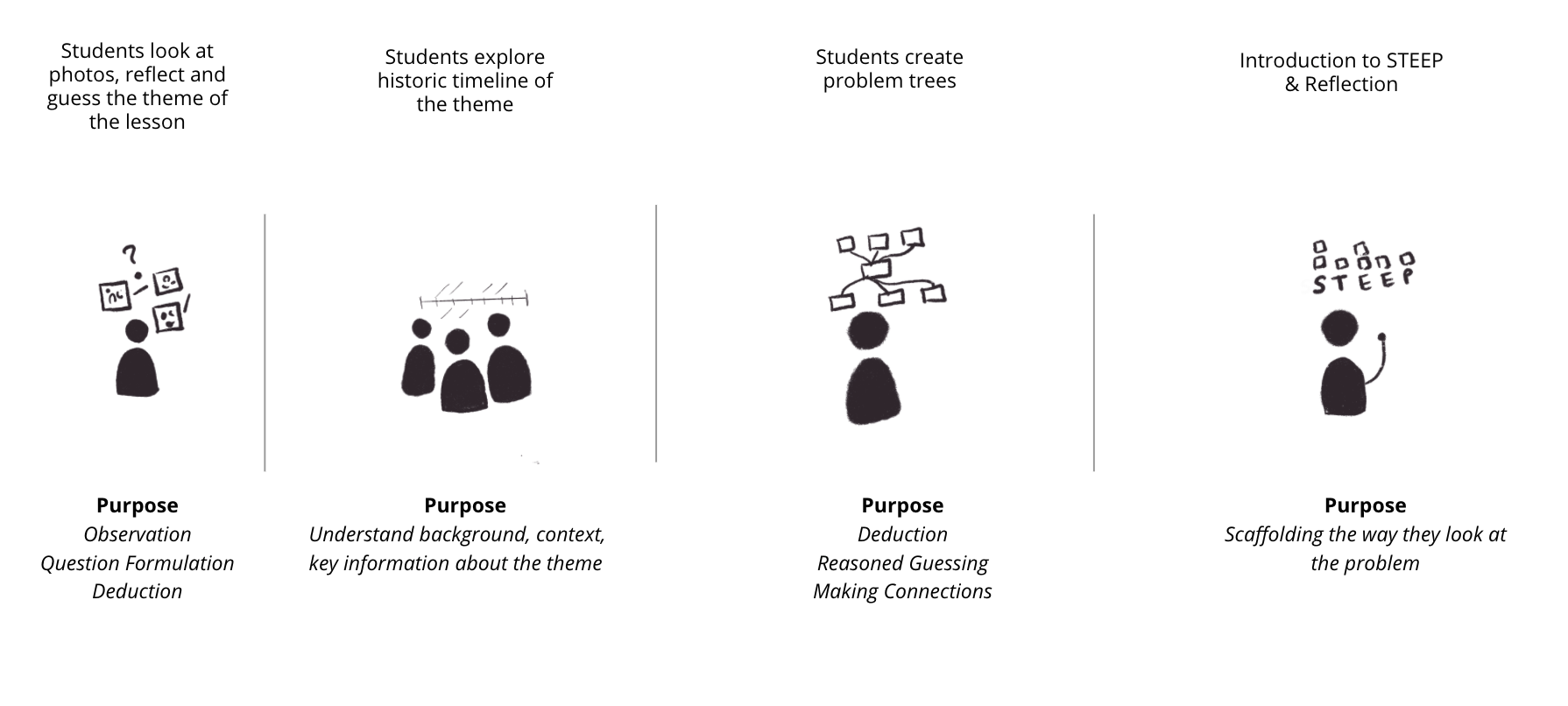

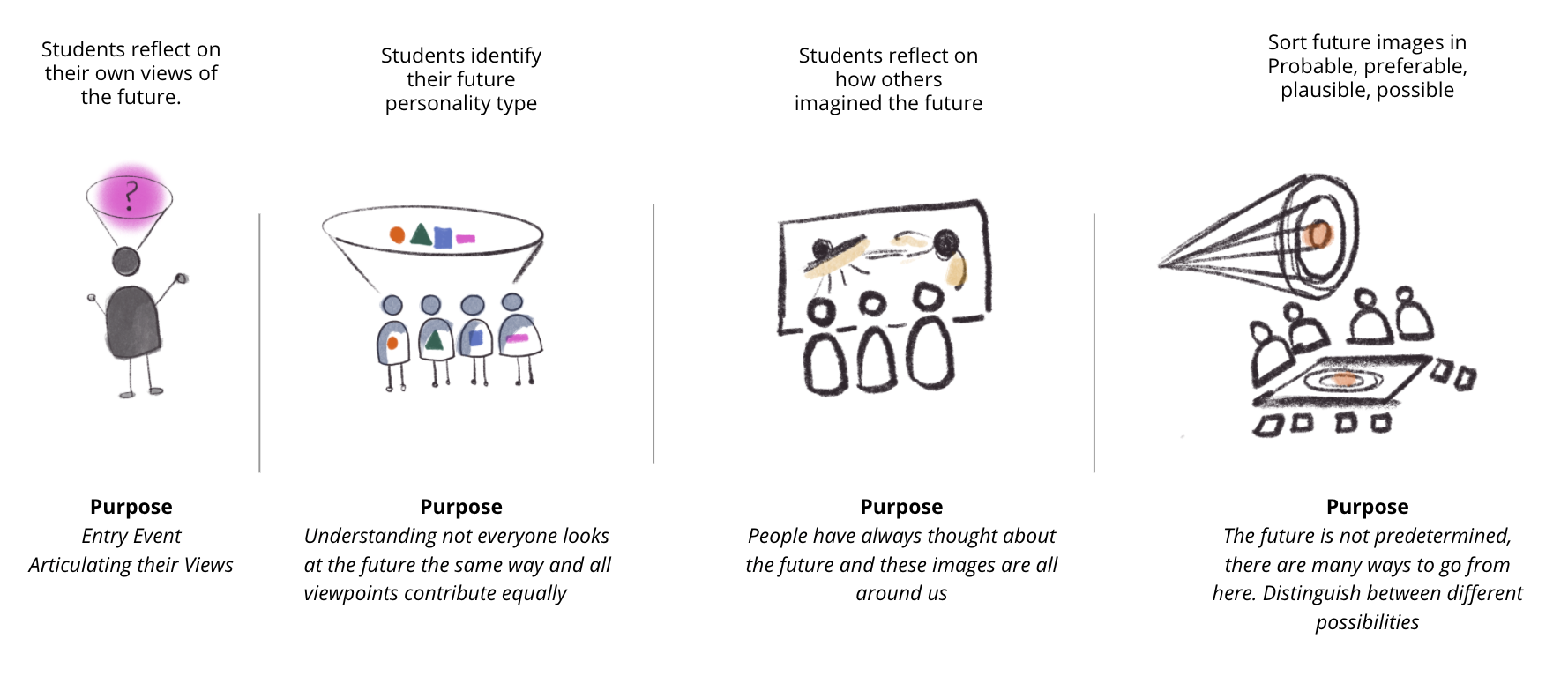

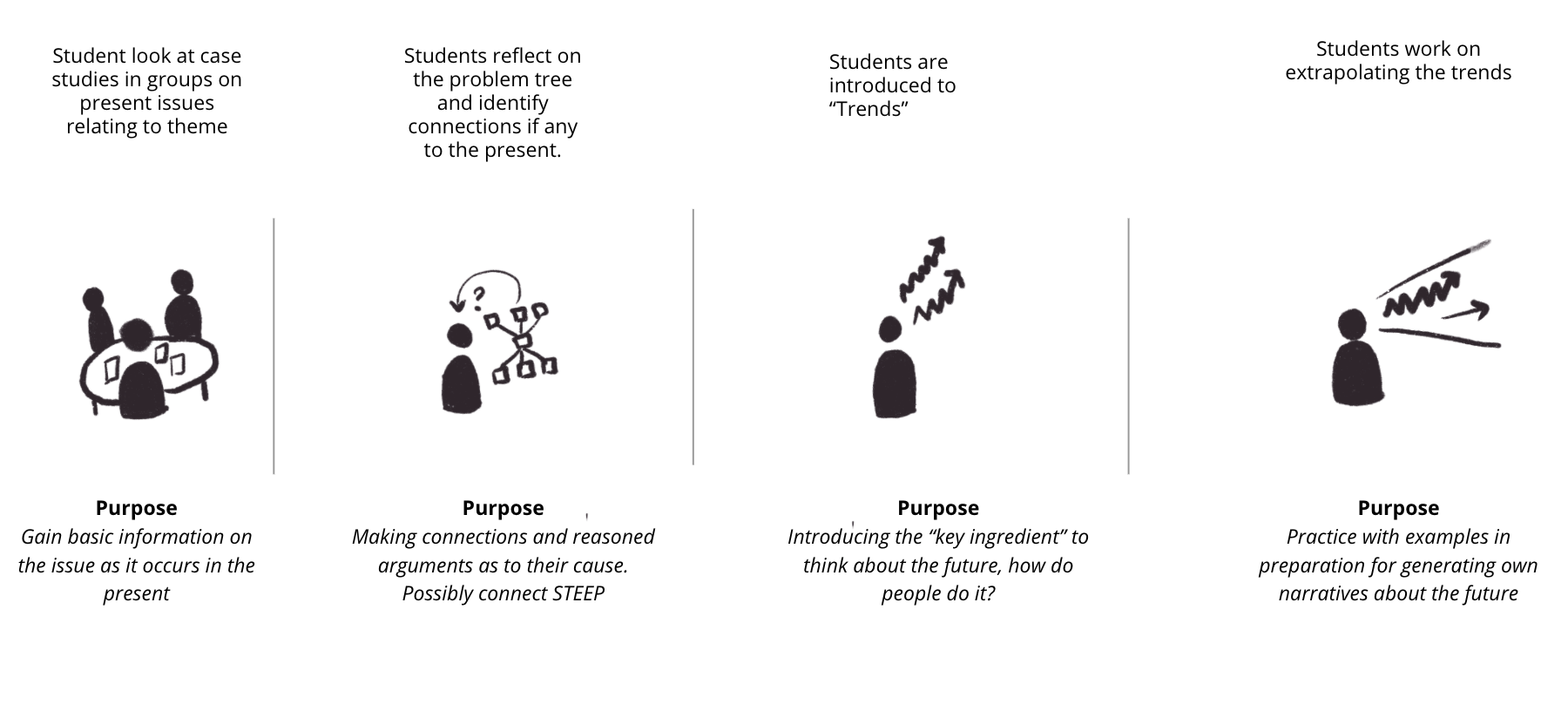

Designing the module: I developed the curricular module in collaboration with the Equitable Futures project, a five-week project-based U.S. history curriculum at the University of Michigan School of Education. The module introduced methods from strategic foresight and speculative design - scenario generation, trend extrapolation, futures card sorts, campaign design - adapted for a high school classroom context. Each activity was designed to move students from surface-level knowledge of historical events toward interpretive and critical engagement with how those events connect to possible futures.

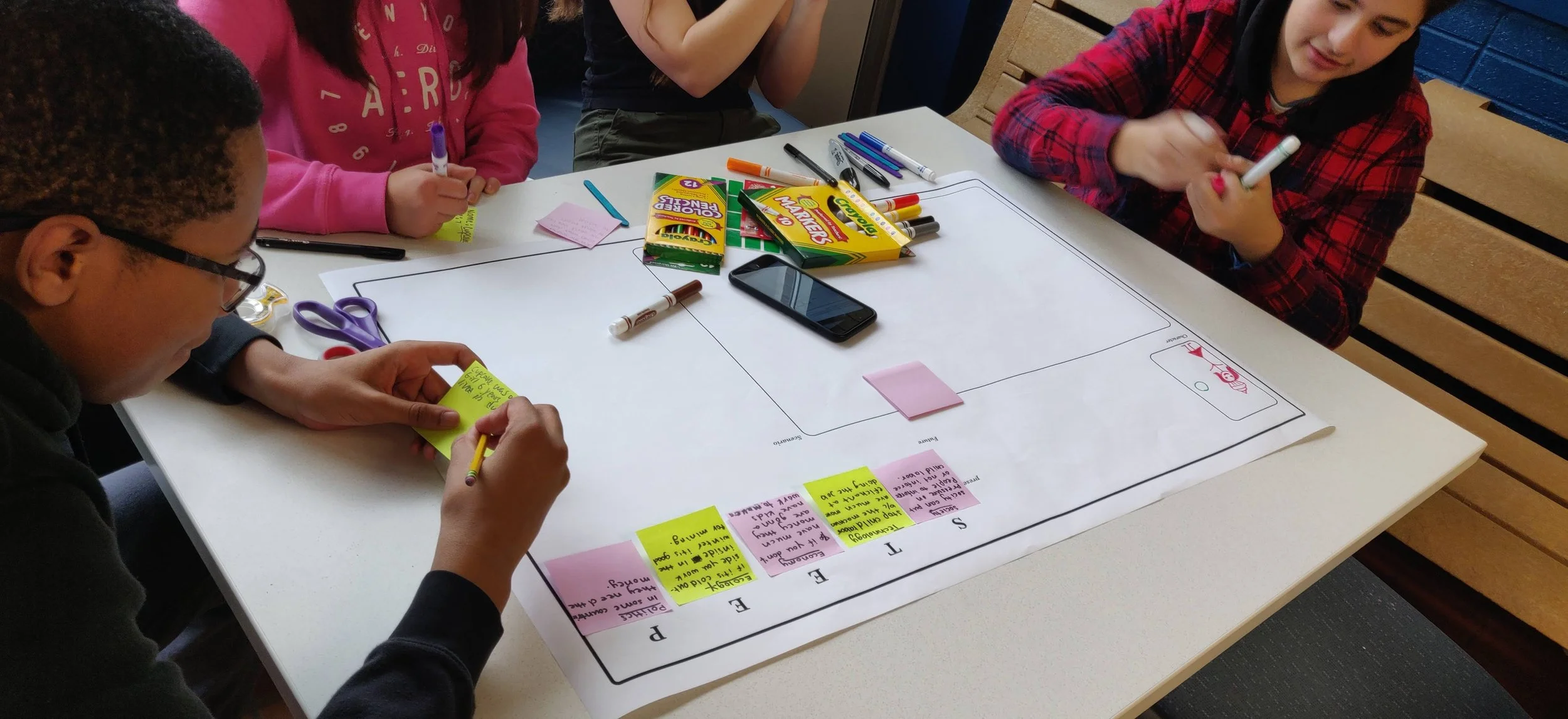

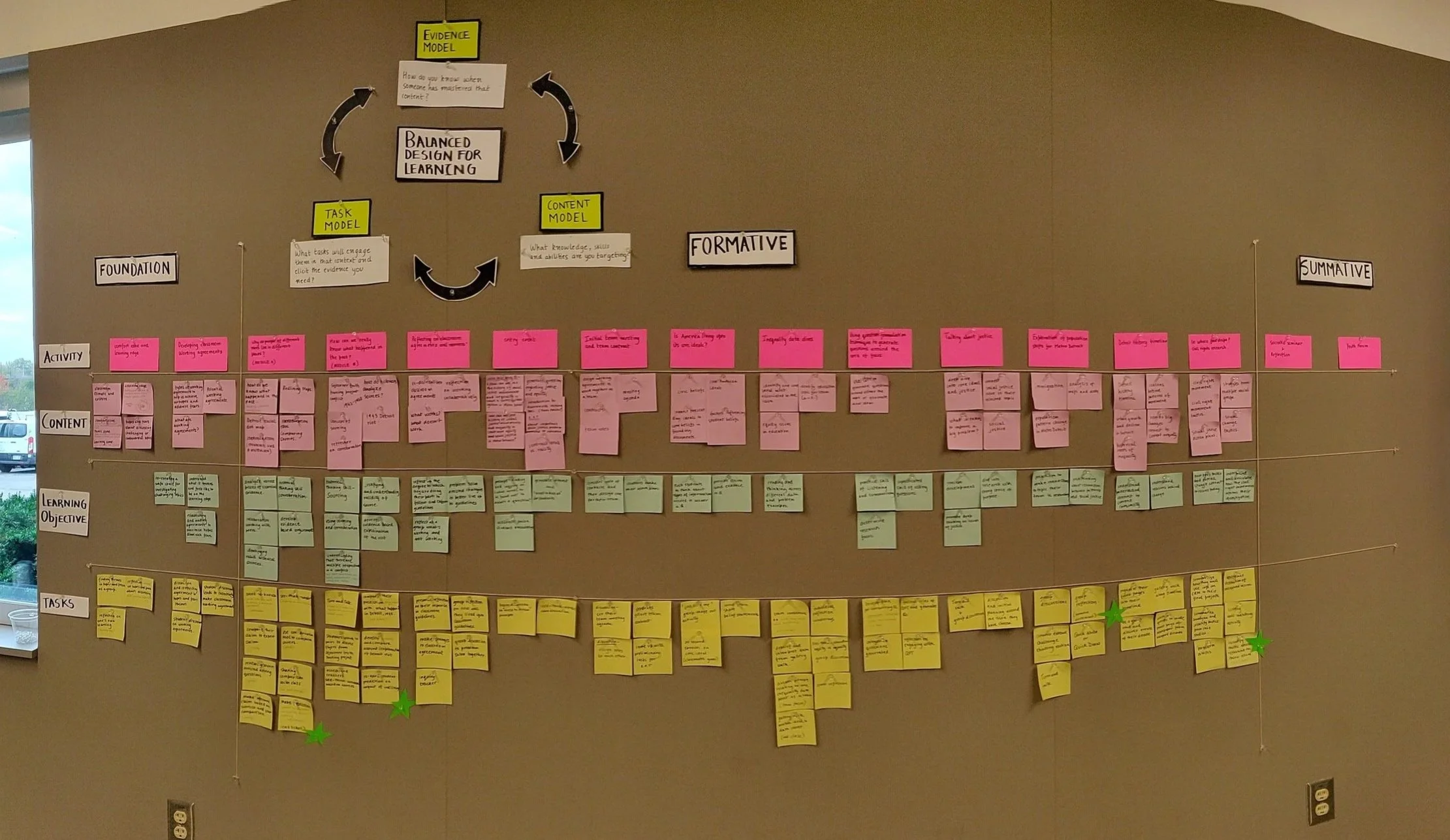

Working with teachers as co-designers:A key finding from the research was that teacher involvement in the design process directly shaped the module's effectiveness. I used card sorting activities with teachers to collaboratively sequence lessons, adapting the module to each classroom's structure, pace, and student needs. This wasn't handing down a curriculum — it was negotiating between what design methods could offer and what worked within real constraints of time, space, and seventy students in a room.

Three iterative cycles:

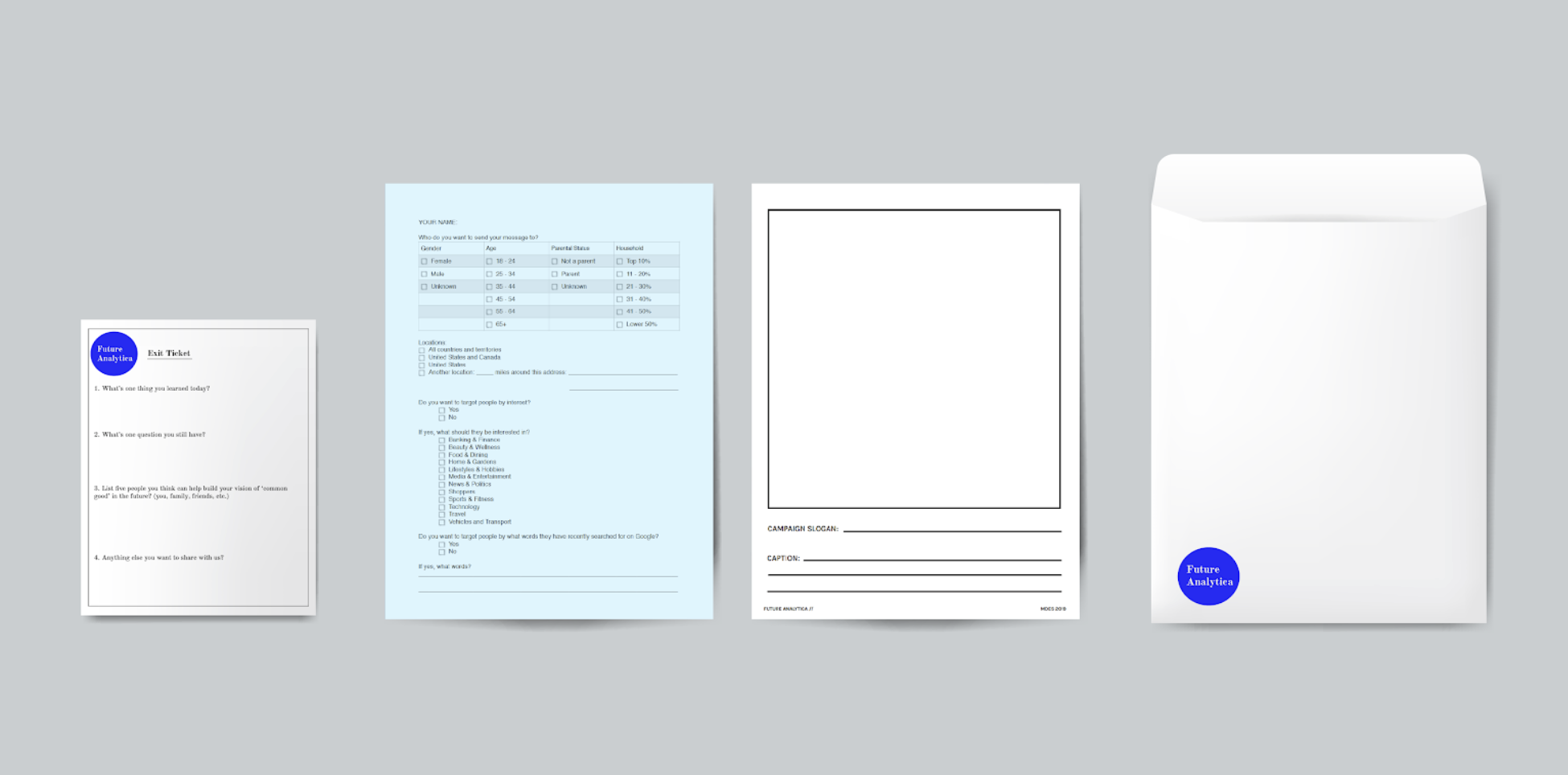

Cycle 1 — Future Analytica (Clarkston Junior High, Spring 2019): Students designed future-oriented advertising campaigns and posted them online, reaching over 138,000 social media feeds globally. The activity subverted the role of youth from passive consumers of online content to creators and disseminators of their own visions.

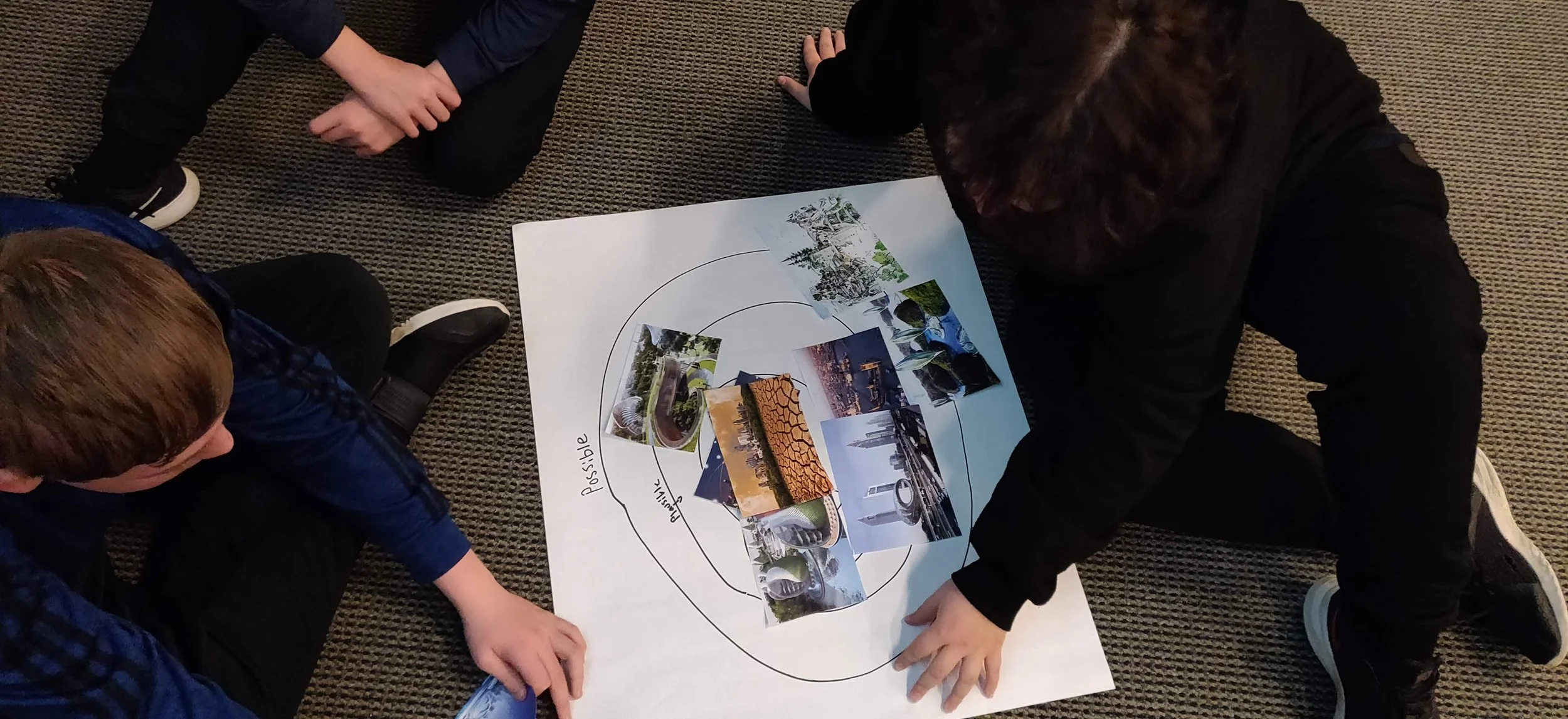

Cycle 2 — Expanded Module (Clarkston Junior High, Fall 2019): A four-part module spanning eight classroom sessions, moving students from a futures primer through historical inquiry, trend identification, and scenario generation. The futures card sort — where students physically sorted images into probable, possible, plausible, and preferable futures — generated the deepest engagement and richest discussion.

Cycle 3 — Embodied Methods (The School at Marygrove, Detroit, Spring 2020): Building on the finding that embodied, playful activities produced more engagement than written prompts, this iteration expanded card-based and movement-oriented methods. Implementation was interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Findings

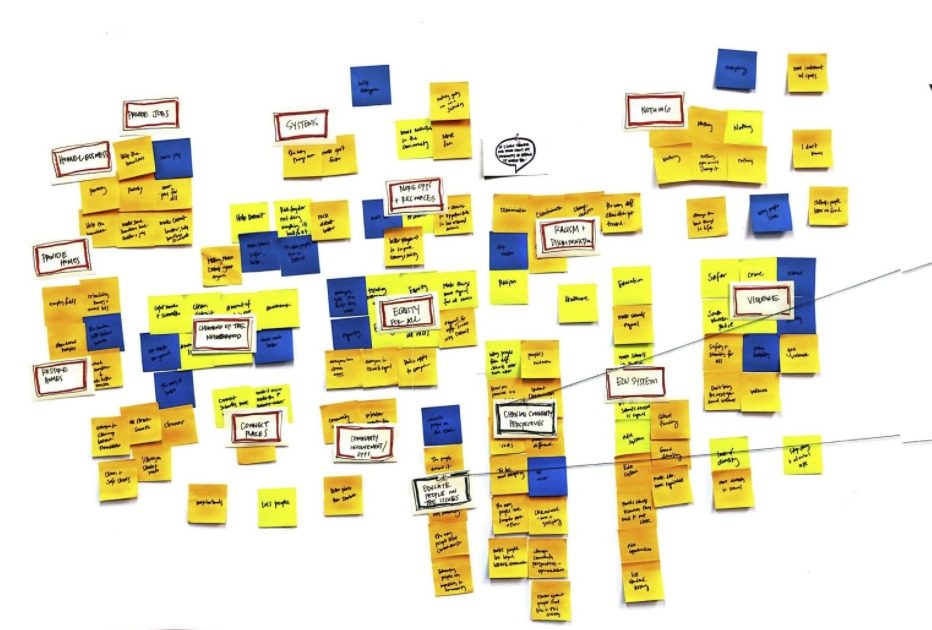

Images of the future vocalize what students care about. Student-generated scenarios, campaigns, and drawings revealed their hopes, fears, and values in ways that standard classroom discussion often doesn't. Five major themes emerged across student artifacts: human connection and belonging, concern for the environment, global politics, physical health, and technological dependence.

Design methods opened new modes of student participation. Visualization, prototyping, and scenario-building gave students tools to externalize complex thinking about change over time. The most generative activities were multimodal - combining visual, verbal, and physical engagement rather than relying on written reflection alone.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to surfacing student agency. Each classroom was a unique ecosystem. What worked in one context needed renegotiation in another. The participatory approach centering both students' and teachers' expertise in the design process was more important than any individual activity.

Teacher collaboration is itself a form of professional learning. The card-sort planning sessions and co-facilitation model created space for teachers to engage with design and foresight methods on their own terms, treating them as co-designers rather than implementers of someone else's curriculum.

Reflection

This project shaped how I approach participatory work with young people. The students didn't need to be taught how to imagine futures- they needed permission and structure. The design methods gave them that. What surprised me most was how readily students connected historical patterns to future possibilities when the activities were designed to support that connection and how much richer the conversation became when it was embodied and visual rather than purely written. It also taught me something I carry into my current research: the methods you choose signal what you believe about your participants. Worksheets signal compliance. Card sorts and campaigns signal that you expect students to think, create, and argue. That methodological choice is itself a statement about youth capacity.

Role: Lead Researcher & Designer (Master's Thesis)

Timeline: 2018 - 2020

Location: Ann Arbor,MI; Detroit, MI; Clarkston, MI

In collaboration with: Center for Education Design, Evaluation, and Research (CEDER) at the School of Education, University of Mi

Methods: Design-Based Research, Participatory Design, Speculative Design, Card Sorting, Scenario Generation, Participant Observation, Artifact Analysis

Advisors: Stephanie Tharp (MID), Kentaro Toyama (Ph.D.), Darin Stockdill (Ph.D.)

Read thesis here